Samuel Taylor Coleridge coined the term “suspension of

disbelief” in 1817, and it refers to a reader’s willingness to enjoy a

fictional story as if the events are really occurring. It applies equally to

realistic fiction and speculative fiction, although one might argue that

introducing fantastic, magical, or science fiction elements in a believable way

adds an extra challenge for the writer. (I’ll address that in Part 2 of this

topic next month.)

In all works of fiction, maintaining point of view is

essential for suppressing the “disbelief” that pulls a reader out of the story. For instance, first person narratives should not break into long

expository paragraphs where the only purpose is to convey information to the

reader that the narrator already knows – and therefore has no reason to

explain. Almost as bad are “As you, know, Bob …” dialogues in which characters

tell each other information they both already know.

Third person narratives should not contain info dumps from

the author that hijack the story – unless that’s the intention, such as in The

Series of Unfortunate Events, where the narrator “Lemony Snicket” is as

much a character as any other in the book. His repeated interruptions to define

a word for the reader or moralize about the behavior of a character are part of

the charm and humor in these books. Likewise, in A Barrel of Laughs, A Vale of

Tears, Jules Feiffer writes as a self-aware story-teller, directly

engages with the reader, and even complains about his characters not sticking

to their planned roles. By contrast, unintentional info dumps and expository

passages stand out to the reader as a clumsy means of conveying back story that

should instead develop organically within the plot.

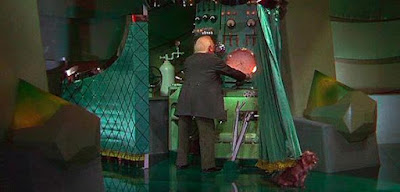

|

| From A Barrel of Laughs, A Vale of Tears: an example of intentional (and humorous) interruption |

Head-hopping is another mistake that breaks suspension of

disbelief and jars readers out of the book. An omniscient point of view should

be carefully planned by an author, and the same goes for multiple points of

view. When this is done correctly, the reader immediately picks up on the idea

that he/she will know the thoughts of many characters – or that different

passages will be seen through the eyes of various characters – and this becomes

part of the suspension of disbelief. Head-hopping, on the other hand, is when

we’ve been following Mary’s viewpoint for fifteen chapters and suddenly there’s

a paragraph where we know what John is thinking about Mary. This never fails to

derail me from my immersion in a story as I wonder: How do we know that?

To sum up, suspending the disbelief of the reader and

providing immersion in the story requires a careful attention to point of view

and presenting information through action, dialogue, and internal thoughts that

always make sense in the context of the story and never in a way that calls the

author out of hiding the way Toto pulled the curtain away from the Wizard.

Next month – How to present fantasy and science fiction

elements while maintaining that suspension of disbelief.

I think I'm jumping ahead to your next blog, but it's amazing how the proper handling of suspension of disbelief properly can get readers to follow things that are normally 'unbelievable.'

ReplyDeleteAnd while it may look effortless in the final, published version of a book, it probably took the author many, many tries to get the balance of fantasy and reality in the right proportion and presented in the correct order.

Delete